11 eDiscovery Best Practices for Defensible Discovery

11 eDiscovery Best Practices for Defensible Discovery

In modern litigation, electronic discovery has become a defining part of how cases are built and resolved. The growing volume of digital evidence means that every step, from identification to production, must be handled with care and consistency.

However, effective eDiscovery depends on more than technology. It’s about process, coordination, and documentation that keep teams aligned and data defensible.

While the best eDiscovery software can indeed make the work faster and more organized, strong results come from having a clear framework and disciplined execution behind every case.

So, in this guide, we’ll explore eDiscovery best practices that can help you manage data accurately, reduce risk, and stay prepared for every stage of discovery.

1. Define a Clear eDiscovery Strategy and Protocol

A clear eDiscovery strategy gives legal teams a structured approach throughout the entire process. It promotes consistency, reduces confusion, and keeps deadlines on track.

The plan should align with the Electronic Discovery Reference Model (EDRM), which outlines the following stages: identification, preservation, collection, processing, review, and production.

When creating your strategy, remember to:

- Set clear goals for scope, timelines, and team roles.

- Document every step to maintain transparency and defensibility.

- Use standard templates for data requests and productions.

- Define escalation points for handling disputes or technical issues.

- Update the plan regularly as laws, lawyer tools, and data sources change.

A written eDiscovery protocol forms the backbone of every matter. It should describe how data will be preserved, how privilege will be protected, and what file formats will be used for production.

This structure keeps everyone aligned from the start and helps prevent missing data or inconsistent handling later.

2. Involve Legal, IT, and Compliance Teams Early

Legal, IT, and compliance teams each play a unique role in managing electronically stored information (ESI), and early coordination prevents confusion later. When these teams work together from the start, identifying relevant data becomes faster and more accurate.

For example, when litigation is anticipated, the legal team defines the scope of discovery and which custodians may hold relevant ESI.

The IT department then identifies where that data lives (perhaps across cloud storage platforms, email servers, or internal systems) while compliance reviews the process to confirm it aligns with privacy and retention policies.

If these groups don’t align early, data could be lost, duplicated, or mishandled, putting the organization at risk of sanctions or missed deadlines.

Many organizations now rely on eDiscovery tools that let cross-functional teams collaborate in real time, centralizing case data and tracking progress from preservation to production.

A shared platform improves communication, reduces manual work, and keeps every department accountable.

For teams seeking a simpler, faster, and more reliable approach to document preparation during discovery, Briefpoint offers automation that turns complex requests into accurate, court-ready documents in minutes.

3. Identify and Preserve Data Sources Promptly

Quick identification and preservation of electronic data are key steps in the discovery process.

Once litigation is expected, legal teams must act fast to locate and secure relevant data before it’s altered or deleted. Delays can lead to spoliation or incomplete productions, both of which can harm a case.

The first step is mapping data sources, which means creating a clear record of where information is stored and who controls it. Common data sources include:

- Company email systems and archives

- Shared drives and document management tools

- Cloud storage platforms like Google Drive, OneDrive, or Dropbox

- Messaging apps such as Slack or Microsoft Teams

- Employee laptops, phones, or external devices

- Social media posts

Once these sources are identified, data collection should begin under defensible procedures that maintain metadata and prevent modification. Preservation notices must also be issued to custodians responsible for the data, suspending any auto-deletion or retention policies.

Plus, documenting each step of data preservation builds credibility and protects against challenges later in court. A consistent, repeatable approach keeps the process transparent and helps the team handle future matters more efficiently.

4. Use Legal Hold Procedures Effectively

A well-managed legal hold process is one of the most important parts of data preservation during discovery.

When a dispute or investigation is anticipated, legal professionals must suspend routine data deletion policies and preserve all potentially relevant ESI. This step prevents the loss of key evidence and demonstrates good faith compliance with the court.

A legal hold begins with a clear notice sent to custodians. Employees or departments likely to have relevant documents or electronic records. The notice explains what data must be preserved, how it should be handled, and who to contact with questions.

For instance, if a company expects litigation involving employment issues, HR staff and managers may receive a hold instructing them not to delete emails, reports, or internal chat messages tied to the event in question.

Tracking acknowledgments and sending reminders are equally important. Every action, from issuing the notice to releasing the hold, should be logged for transparency.

Many legal teams now use automated legal hold software to monitor compliance and record each step. This level of documentation protects the organization and confirms that data was preserved properly if the process is ever questioned in court.

5. Collect Data in a Defensible and Documented Way

Once a legal hold is in place and data preservation is confirmed, the next phase of the discovery process involves collecting that data for review. This transition is critical because any misstep during collection can damage file integrity or cast doubt on the evidence.

Moreover, data collection is one of the most sensitive parts of legal discovery, and every action must be defensible if challenged in court.

Legal teams should apply consistent procedures that maintain authenticity and retain relevant information exactly as it existed. This includes preserving metadata, timestamps, and detailed records of each activity.

Defensible collection often involves coordination between legal and IT teams. Data must be copied from secure data storage systems using approved forensic tools that prevent alteration.

For example, when collecting data from mobile devices, specialists may extract text messages or attachments in a controlled environment to preserve their original state.

A simple collection record may include:

- The person responsible for the collection and the date completed

- The tools or software used

- The source systems, such as email servers or cloud databases

Documenting every action supports strong information governance and demonstrates accountability. In large legal proceedings, complete records protect the organization from disputes about data handling and show that the collection followed a defensible process.

6. Leverage Advanced Search and Filtering Tools

Advanced search and filtering tools are core features of any modern eDiscovery platform. They allow legal teams to narrow large sets of data into smaller, more focused collections that matter to the case.

As data volumes continue to grow across emails, chat logs, and cloud solutions, these tools make it possible to manage the document review stage with precision and speed.

In the modern litigation process, the biggest eDiscovery challenges often involve identifying what’s relevant among thousands or even millions of files.

Keyword searches, date filters, and metadata queries help locate information quickly, while advanced analytics can detect duplicate files or similar content that might otherwise be reviewed multiple times.

Some systems also let users analyze log files or communication patterns to uncover hidden connections between custodians or data sources.

A strong review process combines these tools with attorney oversight to confirm accuracy and context. Automation alone can’t replace legal judgment, but it can remove the manual burden of sorting irrelevant material.

7. Apply Technology-Assisted Review or AI for Efficiency

Technology-assisted review (TAR) and AI-powered review systems have become standard in modern eDiscovery because they help manage the overwhelming amount of digital data generated in litigation.

Essentially, these technologies speed up the review of emails, documents, and messages while maintaining accuracy and consistency in how relevance and privilege are determined.

- Technology-assisted review: Uses machine learning and predictive coding to identify patterns in previously reviewed data, which allows the system to rank remaining documents by likelihood of relevance.

- Artificial intelligence: Expands on TAR by applying natural language processing and contextual analysis to understand meaning, not just keywords, across large datasets.

In practical terms, TAR and legal AI tools learn from attorney input and apply those lessons to new files, which helps teams prioritize what to review first. This reduces manual workload and accelerates the production of electronically stored information.

When used responsibly, TAR can cut review time by more than half and improve consistency in identifying data produced for disclosure. Combined with human oversight, these tools help legal teams meet discovery deadlines efficiently while keeping the process defensible.

8. Maintain Strong Chain-of-Custody Documentation

A clear chain of custody makes sure that every piece of evidence collected during eDiscovery can be trusted.

More specifically, it records how data moves from collection to review and production, showing that nothing was changed, lost, or mishandled. Strong documentation also supports regulatory compliance, especially in industries where audit trails are required.

To keep all teams on the same page, every handoff should be recorded in a chain-of-custody log. This log tracks:

- The names of key custodians involved in handling or accessing data

- The date and time of each transfer

- The storage location and transfer method used

- Verification notes confirming file integrity

For example, if an outside vendor receives a set of emails for review, the record should show when the transfer occurred, who approved it, and how the files were verified before upload. Each action must be timestamped and supported by documentation.

Maintaining this level of tracking not only protects against disputes but also helps in ensuring compliance with legal discovery standards. Courts expect transparency in how evidence is handled, and a reliable chain of custody provides exactly that.

9. Review and Redact Sensitive Information Carefully

During the review phase of eDiscovery, handling confidential data requires both precision and awareness of privacy laws and eDiscovery rules.

Legal teams must identify and redact sensitive content before further processing or production to avoid exposing personal or privileged material. Failure to do so can lead to sanctions, data breaches, or violations of legal requirements.

Examples of information that should be redacted include:

- Personal identifiers such as Social Security numbers or birth dates

- Financial details like bank account or credit card numbers

- Private communications covered by the attorney–client privilege

- Medical records or health-related data protected under HIPAA

One of the most common eDiscovery challenges is maintaining a balance between transparency and confidentiality. Automated redaction tools can speed up the process, but human review is still necessary to verify accuracy and context.

For instance, a legal AI system might flag names or numbers, but only an attorney can decide if they are relevant or privileged within the legal case.

Careful redaction protects both clients and opposing parties, keeping productions compliant and defensible. Every redaction decision should be logged and stored with a record of who approved it, so there is a clear audit trail for future reference.

10. Track Costs and Vendor Performance Throughout the Process

Monitoring expenses and vendor results is an often-overlooked part of the eDiscovery process, yet it has a direct impact on both budgets and case efficiency.

Each stage of discovery incurs measurable costs tied to storage, software licenses, and professional services. So, keeping a detailed record of these figures helps legal teams forecast spending, justify budgets, and identify where savings are possible in future matters.

For example, a law firm working with multiple vendors might notice that one provider charges significantly higher rates for hosting data but delivers slower turnaround times.

Tracking this performance over several projects makes it easier to decide who offers the best value. Metrics like average processing time, accuracy rates, and responsiveness can help build a clear picture of which partnerships are most effective.

Many firms now use dashboards or litigation management software to centralize cost data, automate invoices, and monitor key metrics in real time.

In other words, treating cost and performance tracking as part of the standard workflow keeps the overall eDiscovery process both predictable and efficient.

11. Regularly Update and Refine eDiscovery Policies and Technology

Finally, every organization should treat its eDiscovery policies as living documents that evolve with new data sources, laws, and legal tech software.

Some areas that should always be reviewed include:

- Backup tapes: Make sure retention schedules reflect current storage limits and recovery options.

- Preservation measures: Reassess how data is secured to avoid accidental loss or overwriting.

- Collecting ESI: Verify that approved tools and methods maintain file integrity and defensibility.

- Producing electronically stored information: Confirm that file formats and transfer protocols meet court and client expectations.

Keeping eDiscovery tools and practices updated not only supports compliance but also reduces manual work. Teams that modernize their approach are better equipped to manage complex matters efficiently.

Autodoc, the newest solution from Briefpoint, takes this a step further. It ends manual discovery work by turning productions and case files into ready-to-serve discovery responses (with Bates numbering and page-level citations) in just seconds.

Book a demo and be among the first to automate their discovery responses.

Briefpoint and the Future of eDiscovery

Strong eDiscovery practices are built through structure, collaboration, and the right technology to keep everything moving smoothly. Each stage of discovery, from locating data to preparing final productions, depends on accuracy and clear communication.

And when teams work within a defined system, discovery becomes less chaotic and more predictable.

Briefpoint helps make that happen. It replaces repetitive manual work with automation that drafts, numbers, and formats discovery responses in just minutes. The result is more time for strategy, stronger client outcomes, and less effort spent on administrative tasks.

If you’re ready to simplify discovery and see what faster, smarter document preparation looks like, book a Briefpoint demo today.

FAQs About eDiscovery Best Practices

What is the identification phase in eDiscovery?

The identification phase is the first step in locating potentially relevant data for a case. It involves data mapping, identifying custodians, and determining which systems or devices hold important files. This stage helps create a clear plan for collecting and reviewing information later in the process.

How should law firms handle data from personal devices?

When employees use personal devices for work-related matters, those devices may contain relevant electronic communication, such as emails or text messages. Legal teams must balance privacy concerns with discovery obligations by following clear policies and using defensible collection methods approved by regulatory bodies or the court.

What is the standard retention period for eDiscovery materials?

A standard retention period varies depending on jurisdiction and industry. Most organizations align their retention schedules with local laws or third-party subpoena requirements. It’s best practice to consult internal legal support teams to confirm how long records should be maintained.

Why is production format important in eDiscovery?

Choosing the right production format affects how the opposing party can review and analyze data. Courts often request files in native format, digital form, or electronic format with proper metadata and load files to maintain data integrity and preserve context.

How can firms protect attorney-client communications during discovery?

Firms protect attorney-client communications by marking privileged materials, using privilege logs, and reviewing every document before responding to discovery requests or attempting to obtain discovery. Careful review prevents accidental disclosure and keeps the privilege intact throughout the process.

The information provided on this website does not, and is not intended to, constitute legal advice; instead, all information, content, and materials available on this site are for general informational purposes only. Information on this website may not constitute the most up-to-date legal or other information.

This website contains links to other third-party websites. Such links are only for the convenience of the reader, user or browser. Readers of this website should contact their attorney to obtain advice with respect to any particular legal matter. No reader, user, or browser of this site should act or refrain from acting on the basis of information on this site without first seeking legal advice from counsel in the relevant jurisdiction. Only your individual attorney can provide assurances that the information contained herein – and your interpretation of it – is applicable or appropriate to your particular situation. Use of, and access to, this website or any of the links or resources contained within the site do not create an attorney-client relationship between the reader, user, or browser and website authors, contributors, contributing law firms, or committee members and their respective employers.

5 Top RFP Automation Tools for Legal Teams

5 Top RFP Automation Tools for Legal Teams

Requests for production (RFPs) play a key role in civil litigation. Fundamentally, they give one party the right to ask for specific documents or records that relate to the case, such as contracts, emails, financial files, and more.

These requests are formal and often strict, which means the responses must be complete, properly formatted, and submitted on time. So, when a matter involves hundreds or even thousands of documents, staying organized becomes just as important as the content itself.

But manual work can only take you so far. As caseloads grow, it gets harder to keep up with every draft, review, and edit. That’s why more legal teams are turning to automation.

With the right tools, firms can handle RFPs faster, keep responses consistent, and avoid the common mistakes that come from doing everything by hand.

In the sections below, we’ll break down what this looks like in practice and highlight a few platforms built specifically for legal document production.

What Are Requests for Production?

In most lawsuits, a big part of discovery comes down to requests for production. These are formal legal requests asking one party to provide documents, records, or other evidence that relate to the case.

Essentially, they help both sides understand the facts before going to trial. You might see RFPs asking for things like:

- Contracts or business agreements

- Internal emails or written communications

- Financial statements and transaction records

- Reports, memos, or other supporting documents

If you’re managing a case, you’ll need to review every request carefully, gather the right files, and make sure nothing confidential slips through. Each page has to be labeled and sometimes redacted before it’s shared with opposing counsel.

This process is one of the most time-consuming parts of discovery. It requires close attention to detail and a clear litigation workflow to stay organized. When handled properly, RFPs help both sides exchange evidence fairly and keep the case moving toward resolution.

What Is RFP Automation?

RFP automation uses technology to manage the RFP response process from start to finish with less manual effort. It replaces repetitive administrative work with smart automation software that supports accuracy, speed, and collaboration across legal teams.

RFP automation often includes:

- Automated document drafting: Templates generate responses that follow required formats and case standards.

- Workflow automation: Tasks like review, approval, and version tracking move through the process without delays.

- Artificial intelligence review: AI checks for missing details, detects inconsistencies, and helps improve response quality.

- Centralized collaboration: Teams can review and update documents together, keeping every edit in one place.

This approach reduces human error, organizes large document sets, and keeps discovery work consistent across cases. Additionally, legal teams gain a structured process that keeps everything on track.

Briefpoint brings this approach to life with tools designed specifically for law firms managing discovery and document production.

Book a demo with Briefpoint to experience how automated RFP workflows can save time and support better accuracy in your legal practice.

What Are the Benefits of Using RFP Automation Tools?

After understanding what RFP automation is and how it works, the next question is simple: What difference does it actually make?

Below are some of the main benefits that legal teams see when using RFP automation tools:

Consistent Formatting and Compliance

One of the most overlooked risks in the RFP process is inconsistent formatting. When teams pull content from old files or past submissions, it’s easy to end up with errors like mismatched fonts, broken citations, or incomplete responses.

Luckily, a strong RFP automation platform can solve this by applying formatting rules automatically across each RFP document.

With built-in templates and a central content library, legal teams don’t have to start from scratch or guess what structure to follow. The platform makes sure that every clause, exhibit, and reference is placed in the right order, using the right layout.

It also helps with compliance. By guiding teams through required steps and flagging missing elements during document creation, automation reduces the chance of skipping key details or violating rules for discovery documents.

Smarter Workload Management

Managing RFPs often turns into a long list of repetitive tasks, such as copying old responses, fixing formatting issues, updating document versions, and chasing feedback. These steps might seem small, but they add up quickly and take time away from legal review and strategy.

With RFP automation software, much of that work gets handled in the background. For starters, it means:

- Standard language drops in automatically

- Documents stay organized

- Version tracking happens without extra effort

The process becomes more structured, and progress is easier to follow. Instead of reacting to every task as it comes in, you get a legal workflow that keeps things clear, repeatable, and less stressful.

Improved Team Collaboration

The RFP process often involves input from multiple people, like attorneys, paralegals, and subject matter experts. Without the right tools, this can lead to version confusion, duplicate work, or missed updates. Everyone ends up working in their own silo, which slows things down.

Modern collaboration tools built into RFP automation platforms fix this by letting users work together in real time. Edits, comments, and updates all happen in one shared space, so nothing gets lost.

For example, a senior attorney can review a draft while a paralegal updates dates and attachments. They don’t have to email back and forth, nor do they have to struggle with a version mismatch.

This kind of setup also supports knowledge management, which makes it easier to reuse strong content across cases without starting from scratch.

Working together across the entire RFP process becomes smoother, with fewer gaps and better communication at every step.

Better Accuracy Through AI

Manual review has limits, especially when teams are under pressure or handling large volumes of documents. That’s where artificial intelligence helps improve consistency.

Many RFP automation tools now use natural language processing (NLP) to read and understand written text. This allows the software to suggest relevant answers, spot missing information, and flag inconsistent language before anything is submitted.

The result is high-quality responses that require fewer rounds of edits and reduce the chance of errors slipping through. For firms handling similar requests across matters, AI can even suggest language based on past responses.

That said, AI is not a replacement for legal review. It supports the process but still requires a human to check the final content. Used carefully, though, it can raise the overall quality of every response.

Faster Client Turnaround

The last (but perhaps the most important) benefit of RFP automation is how much faster you can deliver work to clients. When deadlines are tight and expectations are high, speed matters.

Automating repetitive tasks like formatting and organizing attachments removes the bottlenecks that usually slow things down. With AI automation reviewing content in real time, there’s no need for multiple revision cycles or last-minute fixes.

The difference shows up in your delivery. Clients receive accurate, polished responses without delays or excuses. Such a level of consistency builds trust and gives your team more breathing room to handle urgent matters without falling behind.

Best RFP Software on the Market Today

Not all RFP tools are built for legal work, and choosing the right one can make a big difference. Let’s take a look at a few standout options you can consider for your tech stack:

1. Briefpoint

Briefpoint is purpose-built for automating discovery responses and drafting across the full range of civil litigation.

It focuses on requests for production, interrogatories, and requests for admission, supporting both propounding and responding across all U.S. state and federal courts.

What sets it apart is its ability to generate high-quality, jurisdiction-ready documents in just a few minutes, using the details of a complaint or discovery request as the starting point.

Instead of spending hours drafting, formatting, and reviewing responses, legal teams use Briefpoint to cut down manual tasks, speed up turnaround, and maintain consistent quality across every case.

Whether you’re handling one RFP or an entire set of discovery requests, Briefpoint handles the heavy lifting with built-in formatting, objection-aware phrasing, and ready-to-edit templates that follow court rules.

Best Features

- Automated document drafting: Upload a complaint and generate up to 70 tailored RFPs, RFAs, and Interrogatories in under 3 minutes.

- Jurisdiction-ready output: Built-in support for state and federal formatting, captions, numbering, definitions, and timeframes.

- Objection-aware language: Avoids ambiguity, compound structure, and vague phrasing by default.

- Full-cycle coverage: Supports both propounding and responding, so you can manage the entire process in one place.

- Standardized templates: Apply your firm’s preferred language and regenerate content with consistent formatting across matters.

- AI-assisted objections: Draft stronger responses using suggested language and firm-approved objections.

- Integration with Word: Export finished documents directly to Word for final review, signature, and service.

- Secure by design: SOC 2 certified, HIPAA-compliant, and never uses your data for model training.

Want to see how you can automate your RFP documents and discovery responses with consistency and control? Book a demo today!

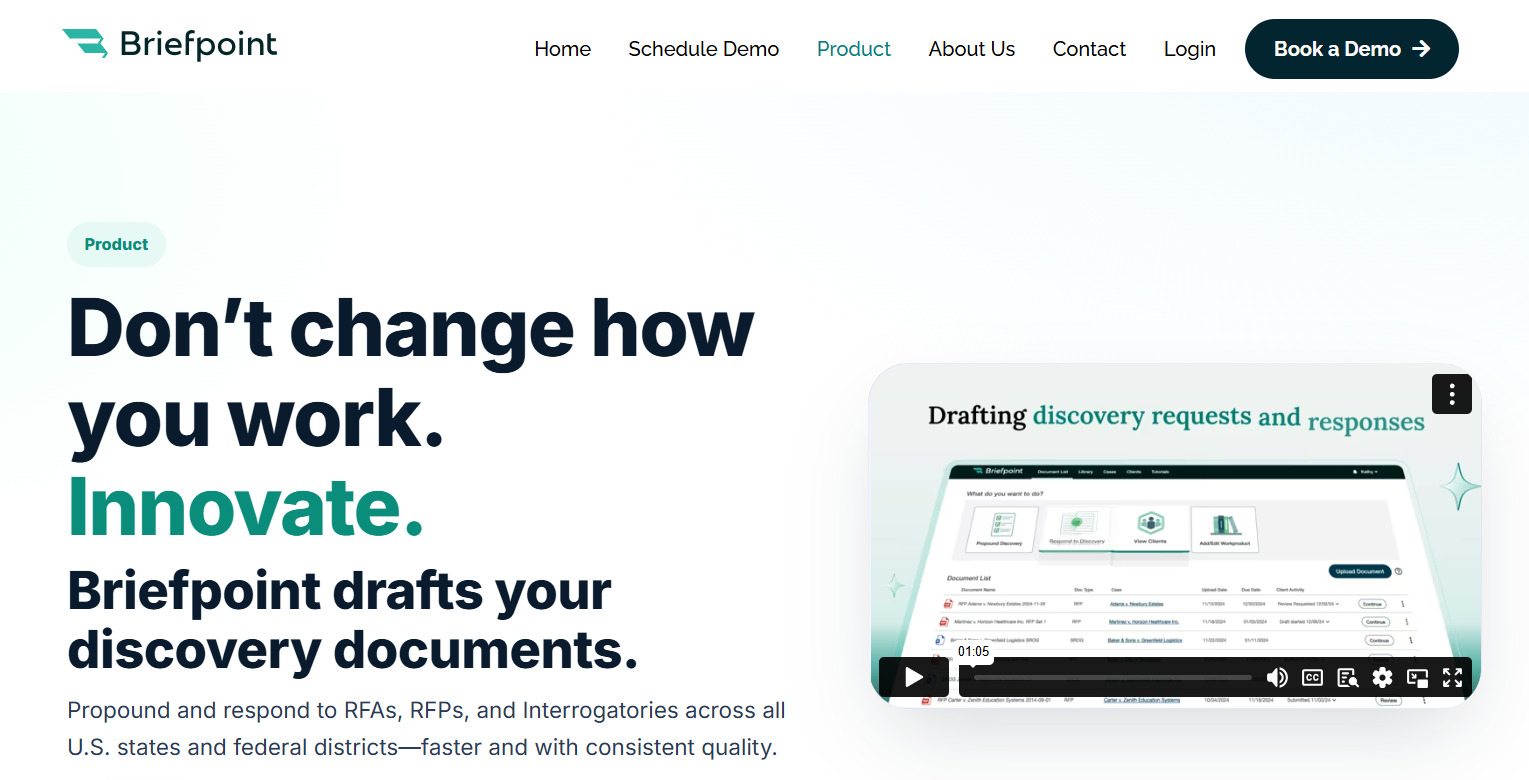

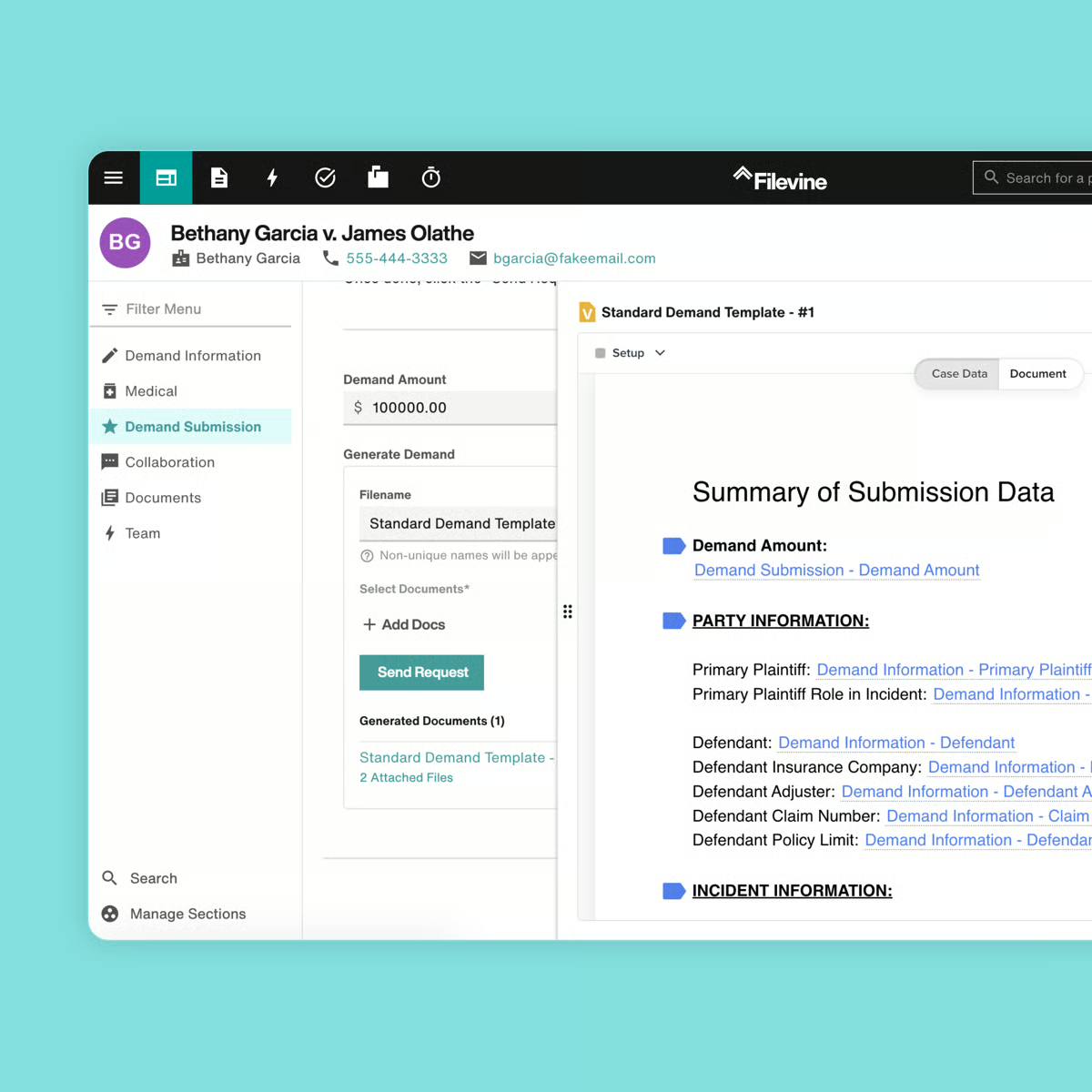

2. Clio Draft

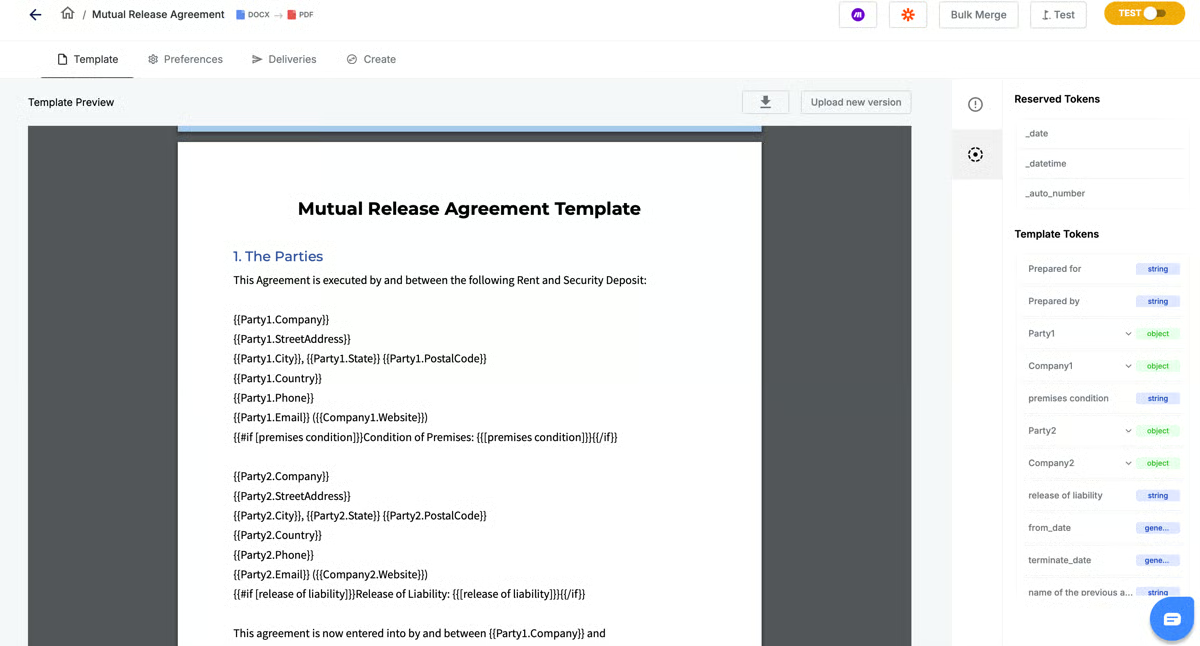

Clio Draft (formerly known as Lawyaw) is part of the Clio ecosystem and focuses on automating document creation for law firms.

It’s suitable for firms already using Clio’s project management or contract management tools, helping keep documents connected to case data and client records.

Source: Clio.com

With customizable templates and built-in logic, Clio Draft supports automated workflows that generate legal documents based on answers to simple form fields. This reduces the need for repetitive editing and keeps files up to date with the latest case information.

It also helps standardize common documents across a firm, which means less guesswork and fewer errors in formatting. While it’s not designed specifically for RFPs, Clio Draft can be useful for building initial responses or handling related correspondence as part of a larger discovery process.

Best Features

- Custom template builder: Create reusable forms with conditional fields to speed up drafting.

- Case data integration: Pulls information directly from Clio case files to auto-fill documents.

- Cloud-based editing: Draft and update documents from anywhere with an internet connection.

- Clio platform sync: Works with Clio Manage and Clio Grow to connect documents with your full client lifecycle.

- Team collaboration: Share templates and drafts with colleagues for real-time input.

- Status tracking: Monitor document progress and make sure each one stays aligned with project timelines.

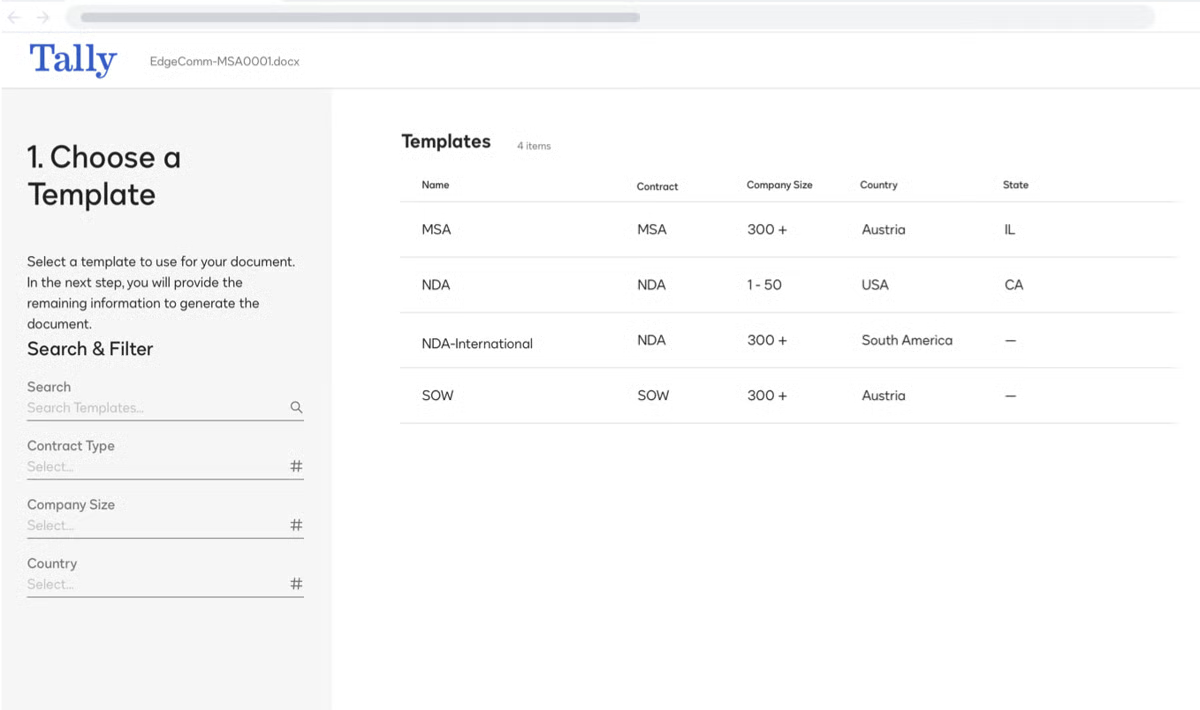

3. Noloco

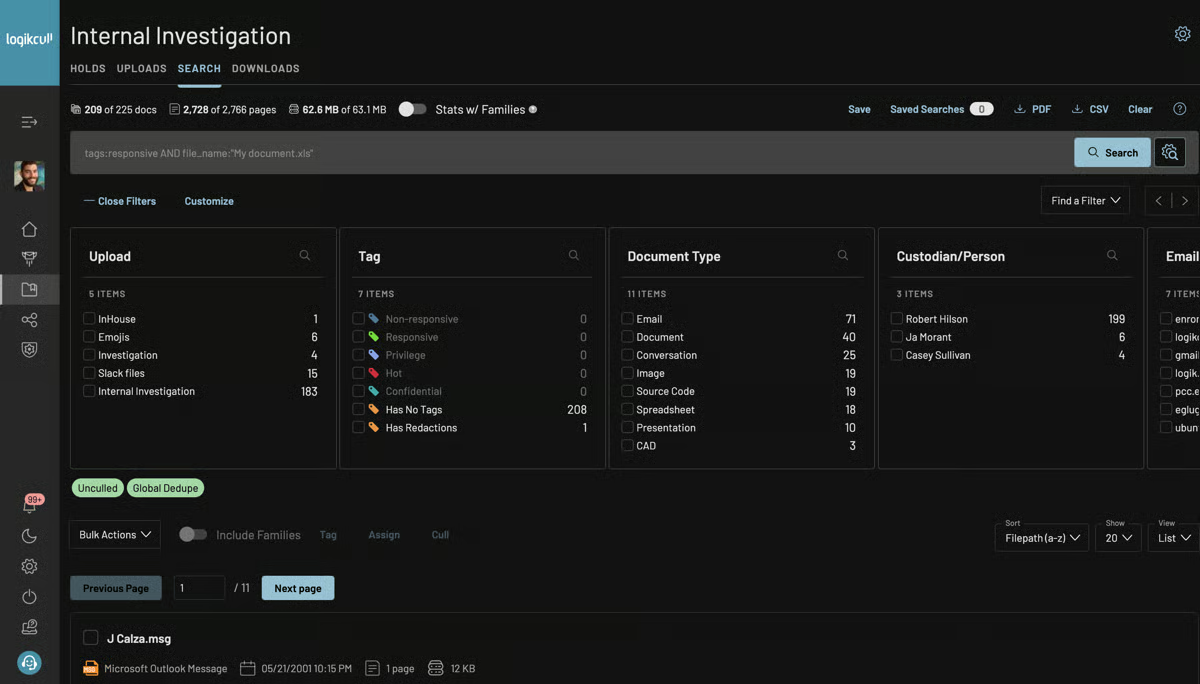

Noloco is a no-code platform that helps legal teams build internal tools for document tracking, task coordination, and client-facing workflows. It’s not built specifically for RFPs, but it can be configured to support the document management and review process behind them.

Source: G2

What makes Noloco stand out is its ability to pull data from existing systems (like spreadsheets, forms, or CRMs) and organize it into a centralized platform. This makes it easier to manage document requests, deadlines, and status updates across multiple matters or departments.

Teams can also build custom apps to handle workflows related to RFP tracking or intake. And with its growing library of AI-powered features, users can add smarter filtering and automation tools to improve consistency over time.

Best Features

- Custom app builder: Design internal tools without code for document tracking, workflows, or intake.

- Data syncing: Pulls live data from sources like Airtable, Google Sheets, or PostgreSQL.

- Centralized dashboard: View tasks, timelines, and document updates in one place.

- Access controls: Set permissions by user or role to protect sensitive case data.

- AI tools: Add logic for document tagging, workflow triggers, or status updates.

- Scalable setup: Adjust layouts and fields easily as team needs grow or future projects shift.

4. Mitratech Legal Document Automation

Mitratech Legal Document Automation is built for legal departments and firms handling high-volume document work. It’s part of Mitratech’s larger suite of legal operations software, which offers scalable support for drafting, collaboration, and approvals.

While it’s often used for contracts and compliance-related tasks, it can also support structured automated processes involved in preparing and managing RFP responses.

Source: Mitratech.com

Mitratech allows team members to collaborate on documents through shared templates and controlled workflows. It pulls relevant content from pre-approved language libraries and adapts it to the context of each matter, which can help teams avoid drafting errors and stay consistent.

Designed with enterprise needs in mind, the platform also includes advanced security features like permission controls, audit trails, and encryption.

Best Features

- Clause library: Store and reuse pre-approved language across different document types.

- Workflow management: Assign tasks and approvals to specific team members with status tracking.

- Template control: Keep templates locked and editable only by authorized users.

- Version tracking: Monitor document changes and restore prior versions as needed.

- Advanced security: Protect sensitive data with built-in encryption and audit logs.

- Enterprise integration: Connects with other Mitratech products and third-party systems for seamless operation.

5. Rally

Rally is a legal workflow platform designed to support document creation, task management, and collaboration within law firms and legal departments.

Although not built exclusively for RFPs as well, its flexible automation features make it a useful option for firms that want to manage document-heavy processes with more structure.

Source: RallyLegal.com

Rally works well for large enterprises looking to unify legal operations across multiple teams. It integrates with existing tools like email, document storage systems, and CRM systems, which helps centralize case and client information.

For firms that handle recurring requests or complex workflows, Rally provides visual builders to map out processes from start to finish.

One of its key strengths is detailed analytics. Users can track time spent on documents, identify bottlenecks, and monitor overall workflow performance. These insights are useful for teams managing RFP timelines across multiple matters.

Best Features

- Workflow builder: Create custom workflows for approvals, drafting, and client communication.

- CRM integration: Connect client data directly to legal projects and document templates.

- Collaboration tools: Assign tasks, leave comments, and track updates in real time.

- Document automation: Populate templates using form-based inputs and conditional logic.

- Analytics dashboard: Monitor time, output, and team performance across matters.

- Cloud-based access: Work securely from any location, with support for remote teams.

The Right Tool for RFP Documents Starts with Briefpoint

Legal work moves fast, and RFP responses leave little room for mistakes. You’ve seen how legal automation can help organize workflows, reduce errors, and speed up delivery, but not every tool is made for discovery.

Many platforms try to cover everything, but fall short when it comes to the details attorneys care about: formatting, objections, and jurisdiction-specific rules.

Briefpoint was built with those details in mind. It’s not a general-purpose automation tool. It’s focused on drafting and responding to discovery documents, including RFPs, with speed and structure that match legal standards across all U.S. states and federal courts.

From objection-aware phrasing to jurisdiction-ready formatting, every part of the process reflects how legal professionals actually work.

If you’re spending too much time reviewing templates, rewording vague requests, or fixing formatting errors, there’s a better way.

Book a demo with Briefpoint and see how much easier discovery becomes when the tool is designed for it.

FAQs About RFP Automation Tools

What is RFP automation software?

RFP automation software is a tool that helps legal teams and other professionals handle requests for production and proposals by automating document drafting, formatting, and tracking. It reduces manual effort, improves consistency, and supports better collaboration across teams. Some platforms also handle related tasks like security questionnaires, intake forms, and template management.

How to automate an RFP process?

To automate the RFP process, start by using a platform that supports RFP templates, content libraries, and rule-based workflows. Upload past responses or build a set of standard clauses, then set up approval steps and document tracking. With the right system, much of the drafting and formatting happens automatically, so you can focus on reviewing and finalizing.

What are the tools used in RFP?

Common RFP response software includes tools like Briefpoint, Mitratech, and Clio Draft. These platforms help with drafting, collaboration, content reuse, and workflow tracking. Depending on your needs, you may also use content management tools or analytics dashboards to monitor performance.

What are examples of automation tools?

Examples include platforms like Briefpoint for legal discovery, RFPIO for sales and procurement teams, and Loopio for knowledge sharing and collaboration. When selecting RFP software, consider features like document automation, template control, and integration with your current procurement process or analytics tools.

The information provided on this website does not, and is not intended to, constitute legal advice; instead, all information, content, and materials available on this site are for general informational purposes only. Information on this website may not constitute the most up-to-date legal or other information.

This website contains links to other third-party websites. Such links are only for the convenience of the reader, user or browser. Readers of this website should contact their attorney to obtain advice with respect to any particular legal matter. No reader, user, or browser of this site should act or refrain from acting on the basis of information on this site without first seeking legal advice from counsel in the relevant jurisdiction. Only your individual attorney can provide assurances that the information contained herein – and your interpretation of it – is applicable or appropriate to your particular situation. Use of, and access to, this website or any of the links or resources contained within the site do not create an attorney-client relationship between the reader, user, or browser and website authors, contributors, contributing law firms, or committee members and their respective employers.

5 Bates Numbering Software Options For The Legal Industry

5 Bates Numbering Software Options For The Legal Industry

Bates numbering has been part of legal work for decades. What began as a manual stamping method is now handled through software that can number thousands of pages in seconds.

For law firms, the ability to assign unique identifiers to every page isn’t optional. It’s how teams keep cases organized and easy to reference.

Bates numbering software takes this process digital. It applies page numbers, prefixes, or codes to entire document sets. This, in turn, makes it simple to cite evidence, share files, and stay consistent across a case.

The shift from stamping machines to automated tools means less time spent on repetitive tasks and fewer mistakes in production.

In this article, we’ll explain what Bates numbering tools are, why they’re valuable for legal teams, and which programs stand out in 2026.

What is a Bates Numbering Tool?

A Bates numbering tool is software used to add unique identifiers, called Bates numbers, to pages in PDF documents. This process, sometimes known as Bates stamping, helps legal teams keep thousands of pages organized and easy to reference.

So, instead of flipping through stacks of paper, legal professionals can quickly locate the exact page they need during discovery, trial, or client work.

With a Bates numbering tool, you can apply custom numbers, prefixes, suffixes, or dates to each page, which makes it simple to track documents across a case. The numbers are placed digitally, so you can edit, batch-process, and format them as needed.

Key features include:

- Adding sequential Bates numbers to large sets of legal documents

- Using custom numbers like client codes or case IDs

- Choosing the placement of numbers on the page (top, bottom, left, right)

- Batch numbering across multiple PDF documents at once

In short, a Bates numbering tool saves time, reduces errors, and gives law firms a reliable system to reference every page in their files.

Let’s take a closer look at the advantages you can expect.

What Are the Benefits of Bates Numbering Software?

Managing thousands of PDF pages can get overwhelming, especially when working on discovery or preparing evidence.

Bates numbering software helps by giving you an easy, intuitive way to add Bates numbers across a single document or even multiple PDF files at the same time.

So, rather than manually stamping every page, you can apply consistent numbering in just a few clicks.

Here are some key benefits:

- Save time: Number large sets of documents in minutes instead of hours.

- Stay accurate: No skipped pages or duplicate numbers thanks to automatic sequencing.

- Customize the format: Adjust the numbering format, add prefixes or suffixes, and adapt to your specific needs.

- Batch processing: Apply numbering to multiple PDF files at once or just a single document.

- Better organization: Clear numbering makes it simple to follow and reference files during legal work.

- Professional results: Clean, uniform stamping that shows preparation and attention to detail.

With these features, Bates numbering software makes it much easier to organize case files, customize numbering, and keep everything consistent across your documents.

5 Best Bates Numbering Software As of 2026

Now that we’ve covered the main benefits of using Bates numbering software, the next step is choosing the right tool. Not every program offers the same features. Some are built specifically for legal professionals, while others are general PDF tools with Bates stamping added in.

To help narrow it down, here are five of the best options in 2026, each with its own strengths depending on your specific needs.

1. Briefpoint Autodoc

Briefpoint Autodoc is changing how litigation teams handle discovery.

For years, lawyers and paralegals have spent countless hours reading through productions, tagging documents, drafting responses, and then manually applying Bates numbers. The process is slow, expensive, and prone to human error.

Autodoc presents a solution to this by automating every step.

Instead of assigning staff to review thousands of PDF pages, you upload your production set along with the RFPs. Autodoc then scans the production tree, finds responsive documents, and drafts complete responses with Bates stamping and page-level citations already in place.

In less than 10 seconds per request, you have a finished, court-ready package: the written responses, the Bates-stamped production, and the citations that tie it all together.

The difference is dramatic. Tasks that once took weeks of manual work are compressed into a single upload. That means your team spends more time on case strategy and less time on repetitive, error-prone discovery tasks.

Key Features

- Automated RFP drafting: Instantly generates responses to every request for production.

- Bates numbering: Applies consistent Bates numbers across productions with no manual stamping.

- Page-level citations: Links each response to the exact Bates-stamped page for defensible accuracy.

- Batch processing: Handles thousands of documents at once, not just a single file.

- One-click packaging: Produces a ready-to-serve response and production set in minutes.

- Speed: Delivers drafts in 3–10 seconds per request to replace weeks of manual review.

For litigation teams, Autodoc is a discovery automation engine. It handles the grunt work so your team can focus on higher-level tasks like building arguments and advising clients.

Join the waitlist for Autodoc to secure early access. If you want to see the core software, book a demo with Briefpoint to see how the platform can transform your discovery workflow.

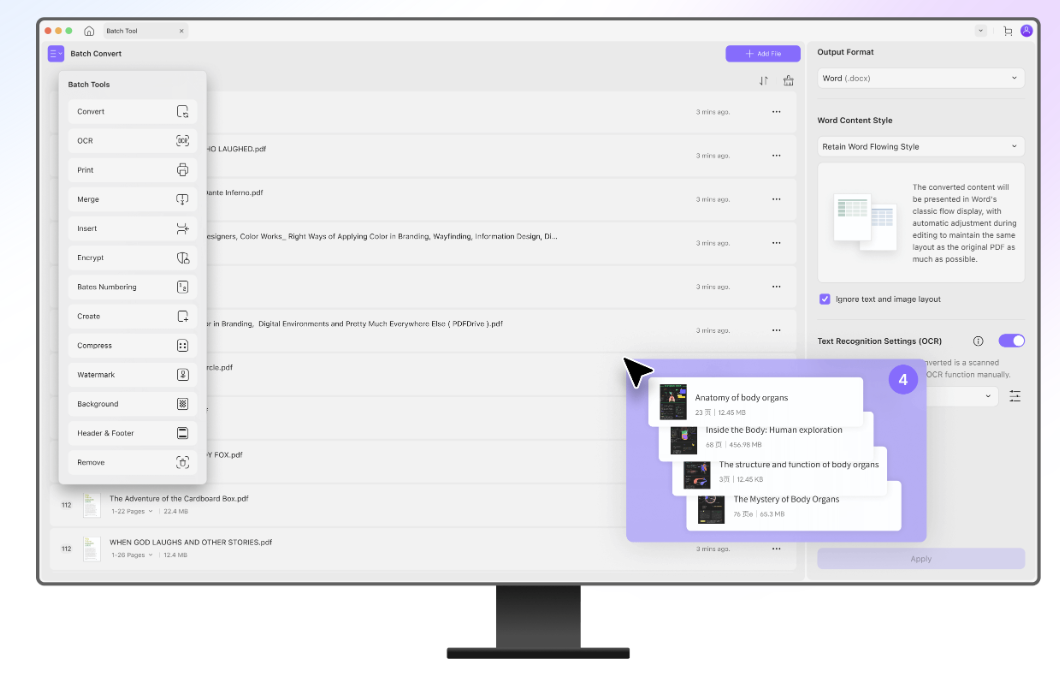

2. UPDF

UPDF is a versatile PDF editor that includes a reliable Bates numbering function. Unlike a heavy suite that may feel overwhelming, UPDF works well as a stand-alone program for firms that need both general PDF editing and numbering tools.

Essentially, it’s designed to handle large volumes of files, which makes it useful for discovery documents or compliance tasks where thousands of pages need to be marked with a page number.

Source: UPDF.com

The software balances ease of use with advanced features, giving users the ability to edit, annotate, merge, and secure documents in addition to numbering them.

Key Features

- Batch Bates numbering: Apply numbering to multiple files at once, saving time on large projects.

- Custom numbering format: Add prefixes, suffixes, or case IDs to match legal requirements.

- Flexible placement: Choose where the page number appears (top, bottom, left, right).

- PDF editing tools: Annotate, merge, and convert PDFs alongside numbering.

- Cross-platform access: Available on Windows, Mac, iOS, and Android.

- Download options: Subscription or lifetime license available.

3. Adobe Acrobat DC

Adobe Acrobat DC is one of the most recognized PDF solutions, widely used by legal professionals and corporate teams. It includes a dependable Bates numbering feature that makes it simple for users to mark documents with a consistent index.

And because many firms already use Acrobat for editing and review, it often serves as the default choice for Bates stamping.

Source: Adobe.com

Acrobat DC is designed to work across different computers and operating systems, which allows teams to collaborate on the same files regardless of their setup. Beyond numbering, it offers tools to edit text, redact sensitive information, and sign files digitally.

The platform also provides options to modify numbering as needed. Users can reset sequences, add prefixes, or adjust placement without reprocessing the entire document.

With its advanced editing suite and integrations, Acrobat DC is suitable for handling large volumes of PDFs where organization and compliance are key.

Key Features

- Bates stamping: Apply sequential numbering across one or many files.

- Custom index format: Add prefixes, suffixes, or adjust number sequences.

- Modify settings: Change placement, font, or numbering without redoing the file.

- Advanced editing tools: Redaction, OCR, and e-signatures included.

- Cross-device use: Works across different computers and platforms.

- License options: Subscription-based pricing for individuals or teams.

4. Aryson PDF Bates Numbering Tool

Aryson PDF Bates Numbering Tool is a dedicated program built specifically for applying Bates numbers to PDFs. Rather than serving as a general editor, it focuses on numbering functions that legal professionals need during discovery and review.

Plus, it can process multiple PDFs at once and gives users full control over numbering details such as prefix, suffix, and starting number.

Source: ArysonTechnologies.com

The software is easy to install and use, so it’s practical for firms that want a straightforward solution without the extras of a full PDF editing suite. Once applied, Bates numbers become part of the file data, so that each version of the document maintains its identifier.

You can also select where the stamp appears (top, bottom, left, right, or center of the page) for consistent formatting across files.

For example, if a firm needs to edit PDFs after numbering, the tool preserves the sequence so the pages remain properly indexed. This is especially useful when documents are created or modified at different times but need to stay in order.

Key Features

- Batch processing: Apply numbering across multiple PDFs simultaneously.

- Starting number control: Choose where the sequence begins for each project.

- Custom placement: Position Bates numbers at the top, bottom, or center of the page.

- Version integrity: Numbers stay with the document even when later edits are made.

- Simple install: Lightweight program that runs without heavy system requirements.

- Practical examples: Apply codes like “CASE123-0001” for quick indexing.

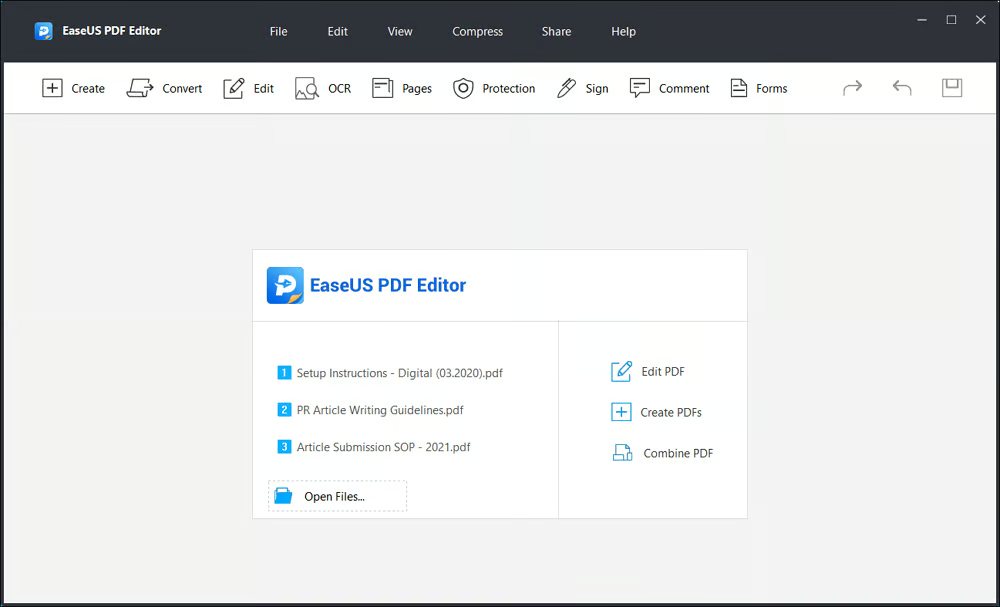

5. EaseUS PDF Editor

EaseUS PDF Editor is a multifunctional program that includes a strong Bates numbering feature along with editing and conversion tools. It’s built to simplify the process of managing legal and business documents and makes it possible to stamp entire productions in just a few steps.

Source: G2

For example, users can drag and drop files from a folder into the software, apply numbering, and process everything at once without complicated setup.

The platform also supports PDF creation, merging, and redaction, which gives legal teams the ability to handle more than just numbering in one interface.

Key Features

- Batch numbering: Apply Bates numbers across entire folders of files.

- Drag-and-drop support: Add files quickly without manual importing.

- Custom formatting: Adjust prefix, suffix, and number placement.

- Editing options: Modify text, redact sensitive content, and merge files.

- Conversion tools: Turn Word, Excel, or image files into PDFs before numbering.

- Free trial: Test the software’s core functions before purchase.

Make Bates Numbering Seamless With Briefpoint’s Autodoc

Most Bates numbering software will help you stamp documents, keep pages in order, and organize large productions. But if you’re handling discovery, you need more than just numbers on PDF pages. You need a way to cut down the time spent reviewing, tagging, and drafting.

That’s exactly where Briefpoint separates itself.

Instead of treating numbering as a side feature, Autodoc builds it directly into a discovery workflow. Upload your production and RFPs, and you get back complete responses with Bates numbers and citations already in place.

If your team is tired of manual review and wants a faster, more reliable system, it’s worth seeing what Briefpoint can do.

Book a demo with Briefpoint and see how Autodoc can change the way you handle discovery.

FAQs About Bates Numbering Software

How to do Bates numbering in Word?

Word doesn’t have a built-in Bates numbering tool, but you can create a manual system by inserting a header or footer with sequential numbers. This method works for shorter files but isn’t practical for large productions. For full automation, dedicated Bates numbering software is the better choice.

Can you Bates number an Excel spreadsheet?

Yes, but not directly inside Excel. First, save the spreadsheet as a PDF, then open it in a Bates numbering program. From there, you can apply numbers, adjust font size, or even add a watermark if needed.

Does Adobe Acrobat have Bates numbering?

Yes. Adobe Acrobat DC includes a Bates numbering feature that lets you apply numbers across multiple PDFs at once. You can drag files into a batch, customize numbering, and even add extra elements like notes or labels to match your case requirements.

How do I do Bates numbering?

The process is simple with the right software. You select one file or a combination of files, choose where the numbers will appear, set the starting number, adjust the style, and then run a preview before finalizing. Some programs may require creating an account for full access, while others let you process documents right away.

The information provided on this website does not, and is not intended to, constitute legal advice; instead, all information, content, and materials available on this site are for general informational purposes only. Information on this website may not constitute the most up-to-date legal or other information.

This website contains links to other third-party websites. Such links are only for the convenience of the reader, user or browser. Readers of this website should contact their attorney to obtain advice with respect to any particular legal matter. No reader, user, or browser of this site should act or refrain from acting on the basis of information on this site without first seeking legal advice from counsel in the relevant jurisdiction. Only your individual attorney can provide assurances that the information contained herein – and your interpretation of it – is applicable or appropriate to your particular situation. Use of, and access to, this website or any of the links or resources contained within the site do not create an attorney-client relationship between the reader, user, or browser and website authors, contributors, contributing law firms, or committee members and their respective employers.

RFP Response Best Practices: 10 Tips for Legal Professionals

RFP Response Best Practices: 10 Tips for Legal Professionals

Handling requests for production (RFPs) is one of the most detail-heavy stages of discovery. Each response demands precision, structure, and coordination across multiple people and systems.

For law firms, the goal is to deliver responses that are accurate, defensible, and compliant with procedural rules.

An effective RFP response depends on a repeatable process that fits your team’s workflow and the client’s needs. Using RFP automation tools can make this easier by reducing manual work and keeping productions consistent.

But to get the best results, we still need to go back to the basics. These are the best practices that make every response reliable and defensible from the start.

In this guide, we will share the 10 RFP response best practices trusted by legal professionals to manage discovery more efficiently.

Understanding the Typical RFP Response Process

The RFP response process can differ across law firms, but the structure stays largely consistent: review, plan, collect, and produce.

This process applies to nearly every firm managing discovery, regardless of size or the client’s industry. The objective is to deliver an effective RFP response that meets all procedural and court requirements while protecting confidential information.

When a request for production arrives, the legal team follows a defined sequence to stay organized and compliant. Here’s how the process typically unfolds:

- Review the request: Read each request carefully to understand its key requirements, including scope, date range, and document categories.

- Identify custodians: Determine which individuals or departments hold the relevant records or data.

- Preserve evidence: Issue a legal hold to suspend automatic deletions and prevent data loss.

- Collect documents: Gather files from servers, emails, cloud systems, and shared drives.

- Review for privilege: Examine each document for sensitive, privileged, or confidential information.

- Produce and log: Deliver responsive materials in the agreed format and maintain a detailed production log.

Although each firm may adjust this sequence to fit its internal systems, following a consistent RFP process helps maintain accuracy, defensibility, and smoother communication between parties.

10 Best Practices For Responding to RFPs

Responding to discovery requests can feel repetitive, but having a clear plan makes the process much easier to manage. These RFP response best practices help you stay organized, protect privileged data, and meet every deadline with confidence.

1. Read Every Request Carefully

It might sound obvious, but this step shapes the quality of your entire response. Every RFP should be read word-for-word, and this means checking for grammatical errors, unclear language, or missing definitions that could create confusion later.

Small mistakes in wording can change the meaning of a request, so it helps to compare it against past RFPs to see if the phrasing or scope has shifted.

Pro tip: Using RFP automation can make this process smoother by highlighting variations, tracking common phrasing, and flagging inconsistencies automatically.

When drafting new responses, note each request’s timeframe, topic, and format requirements. Highlight vague terms like “all communications” or “any records,” since those may need clarification before you begin collecting documents.

Many teams keep a shared tracker for each RFP, which records the assigned attorney, relevant custodians, and upcoming deadlines. That extra step keeps everyone on the same page and prevents inconsistent or incomplete responses down the line.

2. Identify Objections Early

Raising discovery objections early helps set clear boundaries for what will and won’t be produced. It also helps save time later by preventing unnecessary document reviews and disputes.

Courts expect clear, specific objections to every request, especially during propounding discovery, where each party must balance thoroughness with protecting privileged material.

That’s why it’s best to identify potential issues as soon as the RFP arrives rather than waiting until the production deadline approaches.

When reviewing each request, look for areas that might require clarification or limitation. Typical grounds for objection include:

- The request is overly broad or unduly burdensome

- The request seeks privileged or confidential material

- The information isn’t relevant to any claim or defense

- The data has already been produced or is easily accessible elsewhere

You can check out this discovery objections cheat sheet to learn more.

Documenting your objections and discussing them early gives both sides a chance to narrow the scope and focus on what actually matters to the case. You can also share your reasoning with the client to keep them informed and aligned.

Over time, tracking objections across multiple cases provides key insights into recurring issues, which can help your team respond more efficiently and consistently in future productions.

3. Communicate With Opposing Counsel

Clear communication with opposing counsel can prevent misunderstandings that often lead to disputes or duplicate work.

One of the most common mistakes during discovery is assuming both sides interpret a request the same way. Without early discussions, teams might collect far more (or far less) than what’s actually needed, making the process unnecessarily time-consuming.

For example, imagine a case where one side requests “all financial communications.” A quick call between counsel could narrow that to a six-month window and limit it to messages between specific departments.

That small clarification saves days of collection and review, especially for large corporations with thousands of files.

Open dialogue also helps level expectations regardless of company size. Smaller firms might have fewer resources and need more time to respond, while larger organizations may require agreement on custodians or data systems.

These conversations often reveal more insights about how the other side structures their review process, which can guide your own strategy.

4. Preserve Relevant Data

Once an RFP document is received, the first priority is to make sure nothing relevant gets lost or deleted. Preserving data protects your case and builds credibility in discovery.

Legal teams should issue a litigation hold right away to cover all potential sources of evidence. Failing to preserve files can lead to sanctions or weakened positions in court.

Examples of relevant data often include:

- Emails and attachments related to the dispute

- Internal chat messages from platforms like Teams or Slack

- Shared drive files, including spreadsheets, PDFs, and images

- System logs or metadata showing document history

- Archived backups that might store older communications

These bullet points show just how many areas can hold responsive information. The scope of preservation depends on the claims, time period, and other factors such as the client’s data systems and storage policies.

Documenting what’s preserved, when, and by whom creates a defensible record if questions arise later. Taking preservation seriously early in the process helps avoid complications and keeps every RFP response accurate and complete.

5. Collect Documents Methodically

A well-organized collection process keeps your RFP response accurate and defensible. Rather than gathering files randomly, follow a structured plan that aligns with the RFP requirements.

Start by identifying custodians and data sources, then coordinate with IT or discovery specialists to retrieve the information in a consistent format. Keeping a log of when and where each file came from helps maintain traceability if questions arise later.

Referencing previous RFP responses can also make the collection faster. Many firms maintain a content library of common documents, templates, or exhibits used in similar cases.

Plus, reviewing this library before starting a new collection can reveal overlaps or reusable materials, which, in turn, can save hours of unnecessary work.

During collection, avoid mixing responsive and nonresponsive data. Each file should be verified for completeness and categorized by request number or subject. When done methodically, this process prevents missed documents, reduces duplication, and simplifies later review.

6. Review for Privilege and Confidentiality

Before producing any documents, take time to review for privilege and confidentiality. This step prevents the accidental disclosure of sensitive material and maintains the integrity of your client’s case.

Both concepts serve different purposes, but often overlap during document review:

- Privilege protects communications between attorneys and clients that were made for legal advice.

- Confidentiality covers sensitive business, personal, or proprietary information that should not be shared publicly.

For example, an internal email between a company’s general counsel and a manager discussing legal risk would be privileged. Meanwhile, a spreadsheet containing customer data or trade secrets would be confidential. Both should be handled carefully.

Teams often use software filters, tagging systems, or secondary reviews to identify these materials before production. Redactions may be applied to portions of documents that contain protected content while allowing the rest to be shared.

Maintaining a privilege log listing each withheld document, its date, author, and reason, helps keep the process transparent.

7. Use Bates Numbering and Metadata

Consistent numbering and clear metadata are the foundation of an organized RFP response. Bates numbering assigns a unique ID to each page or file (for example, ABC_0001234), helping everyone in the case reference the same document without confusion.

Meanwhile, metadata adds searchable context, like author name, creation date, and file type, which keeps productions transparent and traceable.

Together, these details make document management smoother during review, motion practice, and depositions.

For example, if a deposition witness refers to “the July report,” having the Bates-stamped version (DEF_0004521) lets all parties identify the same page instantly. It also reduces disputes about what was produced and when.

Applying Bates numbers and managing metadata manually, however, can take hours or even days for large productions. That’s where RFP automation tools can change everything.

Briefpoint’s upcoming Autodoc feature eliminates the manual work entirely. It auto-drafts RFP responses, adds Bates numbering and page-level citations, and packages everything for download in just seconds.

Autodoc can process each request in 3–10 seconds, which can turn weeks of discovery work into one upload.

Join the waitlist for Autodoc today. Be first in line to end discovery work for good and let your next RFP production build itself.

8. Produce Documents in the Agreed Format

Another obvious tip, but it’s one that saves endless headaches. Before producing anything, confirm the agreed format with opposing counsel, whether that’s PDFs, TIFF images, or native files with metadata.

Producing in the wrong format often leads to rework, disputes, or even motions to compel. But when both sides understand how files will be delivered, the process moves faster and with fewer surprises.

Every production package should have clear headings and a logical folder structure. Labeling folders by request number, custodian, or topic helps everyone navigate the materials quickly. It also shows attention to detail, which can strengthen your credibility in discovery.

Once everything is reviewed, numbered, and labeled, perform a quick quality check before submission. Confirm that all Bates numbers are visible, metadata is intact, and no privileged files slipped through. This final step helps you feel confident that your production is defensible and complete.

9. Maintain a Production Log

Keeping a production log may seem routine, but it’s one of the simplest ways to improve quality and accountability in discovery.

A well-maintained log tracks what was produced, when it was delivered, and to whom. This creates a complete record that can be referenced if any issues arise later. It also makes rolling productions easier to manage and keeps your team aligned across multiple requests.

Your production log should include details like:

- Production date – When the documents were sent to opposing counsel

- Bates range – The specific numbering sequence for that batch

- Recipient – The party or firm receiving the production

- Description – A short summary of what that production includes

- Notes – Any clarifications or special handling instructions

These entries might seem small, but together they build a clear trail of accountability. Over time, analyzing your logs can also highlight recurring issues or inefficiencies that your team can fix to improve quality in future productions.

10. Review Responses Before Submission

Before sending anything out, take time to review every RFP response for accuracy and consistency. This final check ensures that objections align with what’s been produced and that no privileged or confidential documents were accidentally included.

Cross-check your production against the submission instructions from opposing counsel or the court. Make sure the file formats, naming conventions, and delivery methods match what was agreed upon.

If the instructions specify a secure portal or particular labeling method, confirm that everything meets those standards before sending.

Many teams assign a second reviewer (someone who hasn’t worked on the earlier stages) to spot inconsistencies or missing files. Reviewing responses with fresh eyes helps catch small errors, such as broken Bates sequences or mislabeled folders.

Once the review is complete and the package matches the submission instructions, you can send it off knowing your production is accurate and ready for review.

End Manual Discovery Work For Good With Briefpoint

Responding to RFPs is demanding work, especially when you’re managing dozens of requests, tight deadlines, and thousands of pages. Following these RFP response best practices helps create a process that’s consistent, defensible, and less stressful.

The more structure and documentation you build into your legal workflow, the more control you’ll have over accuracy and turnaround time.

But even the best manual process still takes hours of review and organization. Briefpoint was designed for exactly this kind of work.

Built for real legal teams, Briefpoint automates drafting and document preparation so you can focus on the parts of discovery that truly need your expertise.

And now, with Autodoc, Briefpoint is taking discovery automation to the next level. Autodoc turns productions and case files into ready-to-serve discovery responses, complete with Bates numbering, page-level citations, and auto-drafted RFP answers in just seconds.

If you’re ready to save weeks of manual review and make your next production effortless, join the waitlist for Autodoc and be first in line to end discovery work for good.

Want to see how Briefpoint works? Schedule a demo today.

FAQs About RFP Response Best Practices

What are examples of good RFP responses?

Good RFP responses are clear, consistent, and supported by evidence. They reference the exact documents or Bates numbers, explain objections precisely, and show organized handling of materials. Strong responses also follow repeatable steps, making it easy for teams to stay consistent across different cases.

How to structure an RFP response?

Start with the request number and a short, direct answer. Then cite the responsive documents, note any objections, and briefly describe what was produced or withheld. Keeping a uniform structure across all responses helps reviewers follow along easily and minimizes confusion during discovery.

What should you not do when responding to an RFP?

Avoid vague objections, incomplete answers, or inconsistent numbering. Never skip privilege review or submit files in the wrong format. These small mistakes can cause disputes or delay the case, especially when opposing counsel challenges the response.

What is the RFP response process?

The process includes reading each request, identifying objections, preserving and collecting data, reviewing for privilege, and producing documents in order. Many firms assign roles, such as reviewers, collectors, and quality checkers, to make this process faster and more accurate across large cases.

The information provided on this website does not, and is not intended to, constitute legal advice; instead, all information, content, and materials available on this site are for general informational purposes only. Information on this website may not constitute the most up-to-date legal or other information.

This website contains links to other third-party websites. Such links are only for the convenience of the reader, user or browser. Readers of this website should contact their attorney to obtain advice with respect to any particular legal matter. No reader, user, or browser of this site should act or refrain from acting on the basis of information on this site without first seeking legal advice from counsel in the relevant jurisdiction. Only your individual attorney can provide assurances that the information contained herein – and your interpretation of it – is applicable or appropriate to your particular situation. Use of, and access to, this website or any of the links or resources contained within the site do not create an attorney-client relationship between the reader, user, or browser and website authors, contributors, contributing law firms, or committee members and their respective employers.

5 Everlaw Competitors That Help Legal Teams Work Smarter

5 Everlaw Competitors That Help Legal Teams Work Smarter

eDiscovery software is no longer optional. Now, it’s the foundation for how modern law firms manage litigation.

Tools like Everlaw have gained a strong foothold in the legal tech space by offering advanced features for reviewing, organizing, and analyzing case data. But as useful as Everlaw is, it’s not always the perfect match for every team.

Some firms need more flexibility. Others want something simpler, more affordable, or easier to train on. That’s why many legal professionals are now looking at Everlaw competitors: platforms that deliver similar value but in ways that better fit their needs.

Let’s take a look at some of the best ones.

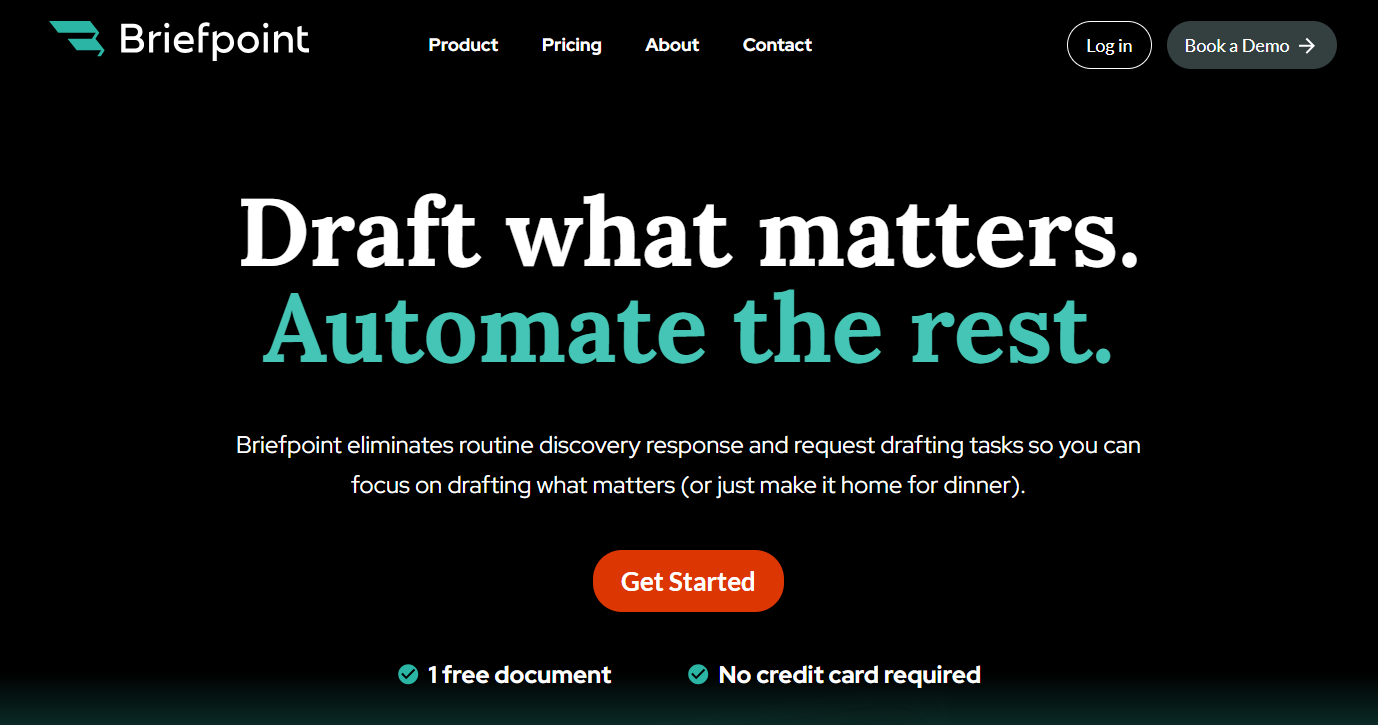

What is Everlaw?

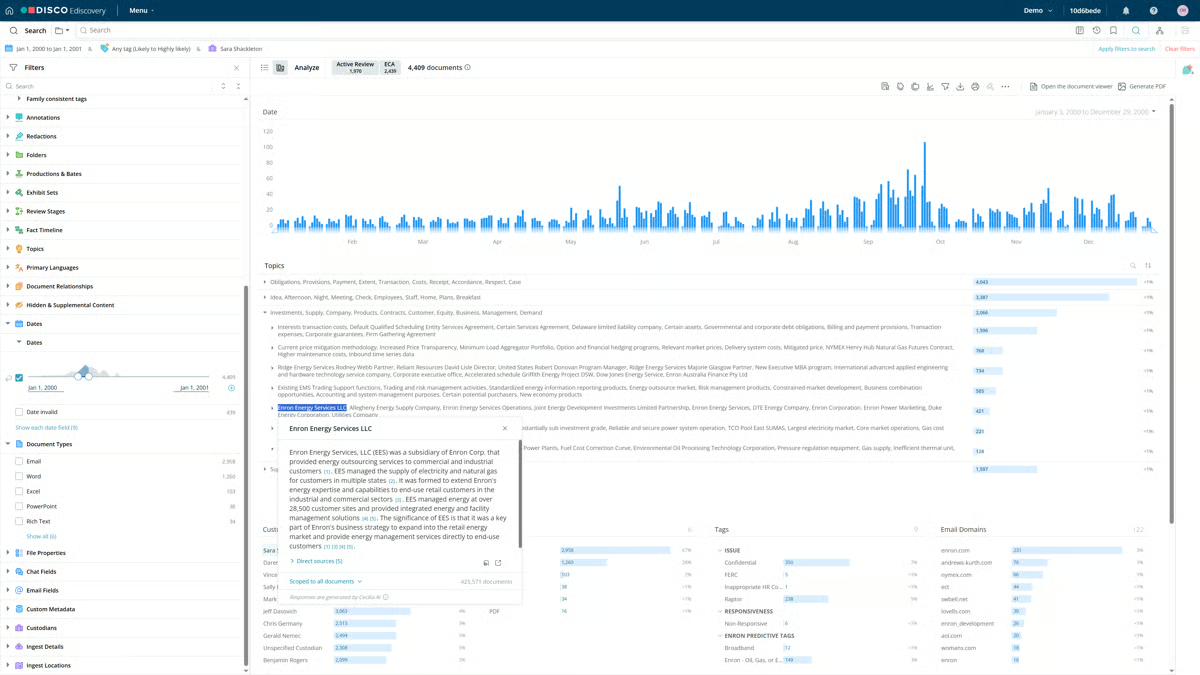

Everlaw is an eDiscovery and litigation software designed to help legal professionals manage the complex process of handling electronic data during lawsuits, investigations, and regulatory matters.

For many attorneys, the challenge isn’t just the volume of documents but finding the relevant information quickly enough to support their case.

Everlaw addresses this by giving teams organized tools for data management, document review, and case preparation, all in one secure platform.

Source: G2

Litigation often involves millions of files ranging from emails to spreadsheets. Without the right system, reviewing this data can consume hours of valuable time.

Everlaw makes the process more manageable with advanced search tools, tagging features, and collaborative review. This usually helps attorneys complete due diligence faster and more reliably.

And because it’s cloud-based, attorneys can access and share information securely, even when working across different offices.

Key Features

- Advanced document review: Attorneys can filter, search, and tag documents at scale, which helps them identify relevant information faster.

- Data management: Handles large sets of electronic data while keeping files organized and easy to access.

- E-discovery workflow: Provides end-to-end support for the eDiscovery process, from document collection through review and production.

- Collaboration tools: Legal professionals can share notes, comments, and highlights within the system.

- Story-building and timelines: Helps teams connect evidence to case strategy, improving how arguments are presented.

- Secure cloud platform: Meets strict security standards while allowing remote access across different devices.

Why You Might Want an Alternative to Everlaw

Everlaw is respected in the litigation and eDiscovery space, but it may not fit every situation. Different law firms and corporate legal teams have unique needs when it comes to data processing, regulatory compliance, network security, and much more.

While Everlaw offers a strong set of tools, many attorneys and legal departments look for alternative solutions that better match their workflows, budgets, and case requirements.

Here are some common reasons professionals consider Everlaw competitors:

- Cost concerns: Many law firms need scalable pricing options that align with smaller cases or limited budgets.

- Complexity of features: Advanced technology is valuable, but teams with lighter caseloads may prefer simpler solutions with a shorter learning curve.

- Scalability issues: Not all firms handle massive document sets, so paying for enterprise-level tools isn’t always practical.

- Regulatory compliance: Some organizations require platforms with specialized compliance certifications or region-specific hosting.

- Data processing flexibility: Alternatives may offer faster or more customizable workflows for ingesting and reviewing electronic data.

- Support and training: Personalized onboarding and responsive customer service can be deciding factors for firms with limited tech staff.

- Network security options: Some competitors provide additional hosting or security controls beyond Everlaw’s cloud-only model.

If your firm wants an alternative to expensive eDiscovery solutions, Briefpoint’s Autodoc offers a smarter path forward.

It automates the creation of discovery documents and litigation drafts directly from reviewed data. However, you don’t get the steep costs or complexity of traditional platforms.

5 Top Competitors of Everlaw

If Everlaw feels like more than what your team needs, you’re not alone. Many law firms look at other options that make eDiscovery and litigation solutions easier to manage, and a few competitors stand out as strong alternatives:

1. RelativityOne

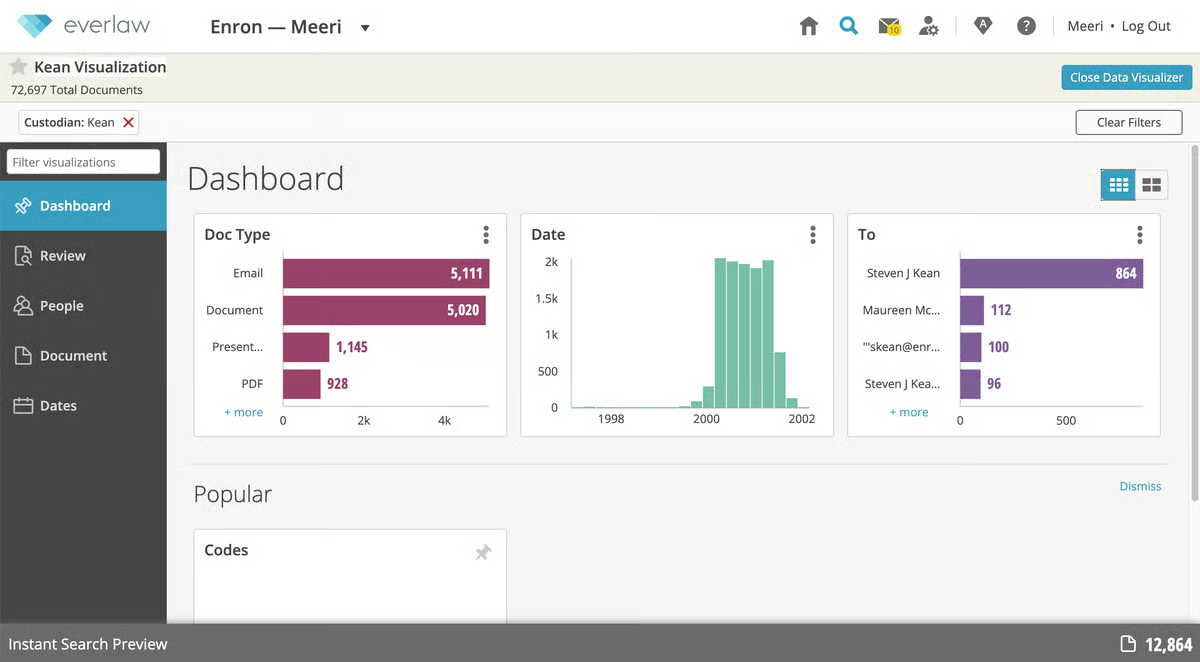

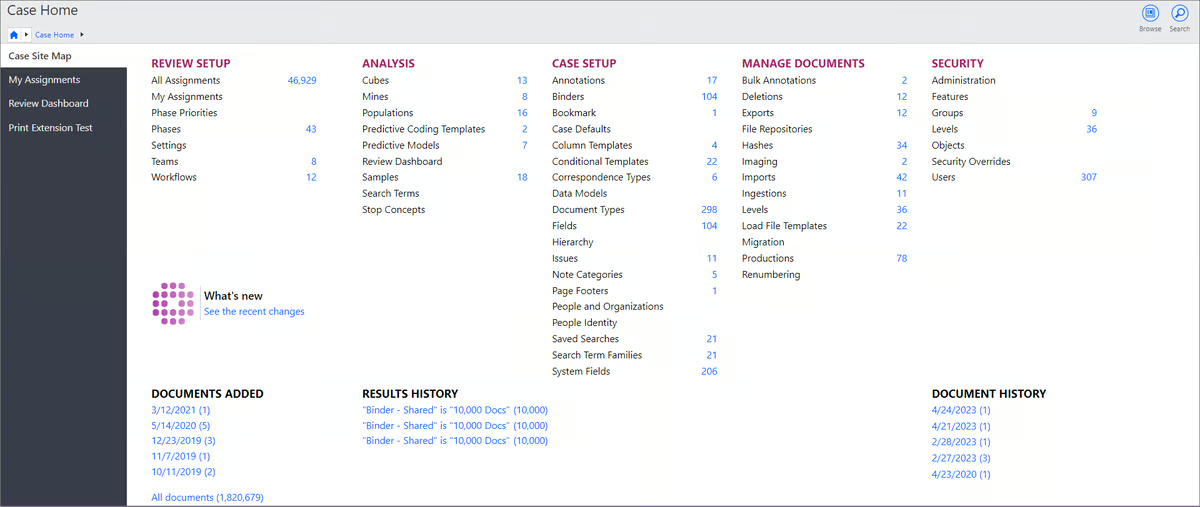

RelativityOne is one of the most widely recognized eDiscovery platforms in the legal industry. It’s used by top law firms and corporations that need reliable tools for managing large-scale litigation and investigations.

Source: Relativity.com

Known for its ability to handle massive data sets, RelativityOne offers flexibility for teams that must review, search, and produce documents under tight deadlines.

The platform also supports information governance and compliance, which makes it valuable for organizations that deal with sensitive or regulated data.

With its strong infrastructure and advanced features, RelativityOne has become a go-to choice for teams needing a complete system that covers everything from early case assessment to final production.

Best Features

- Early case assessment: Helps attorneys quickly filter large data sets to focus only on the most relevant information before moving deeper into review.

- Artificial intelligence: Uses predictive coding and machine learning to speed up document categorization and review.

- Information governance: Offers tools for monitoring, securing, and organizing data across departments and cases.

- Flexible document production: Built-in features simplify how teams prepare and produce documents for litigation or regulatory matters.

- Global scalability: Designed for corporations and firms handling cases across multiple regions and jurisdictions.

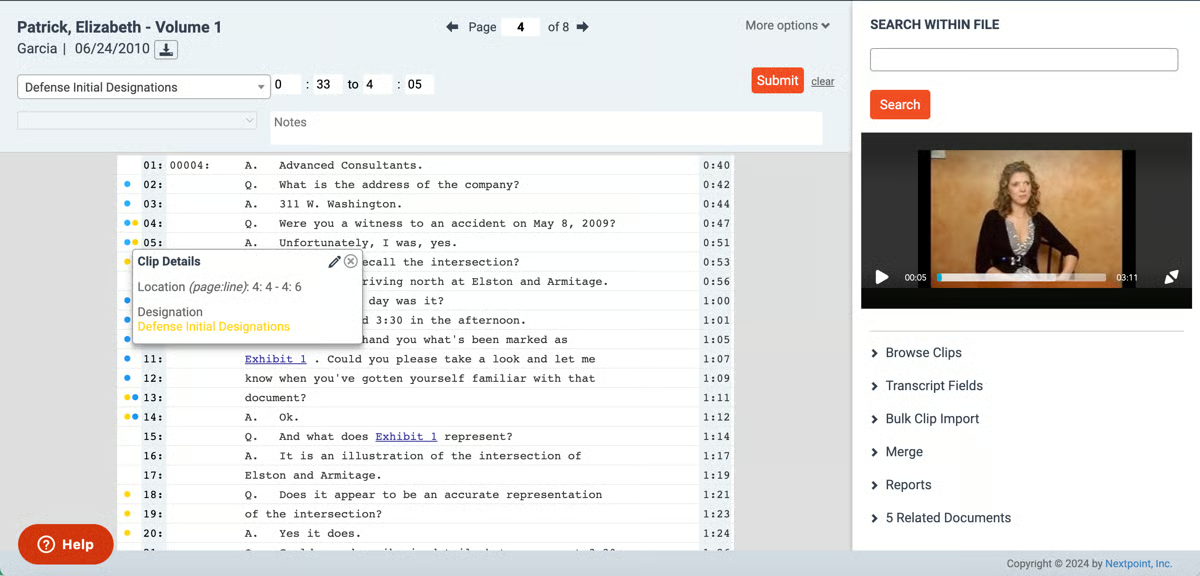

2. Nextpoint

Nextpoint is a cloud-based software built for eDiscovery and trial preparation, designed to support law firms, corporations, and even government agencies that want a more affordable option than larger enterprise systems.

Unlike many complex tools, it aims to give attorneys practical case management features without overloading them with unnecessary steps.

Source: G2